|

Halloween is not a universal instinct. It is a learned behavior practiced by a specific human community at a particular time in their history. Therefor, it is not worthy of discussion. "Mr. Grumbles, make a fire," said the raven perched on a troll's shoulder. His name was General Graa.1 "I will skewer snacks for roasting," said the giant spider, whom we shall call Hostess. "Let me gather rocks to heat for a mud-bath," said the bug-eyed monster, Twine. "A lovely idea," said Digeridoo the sea-beast. "I'll dig out a wallow for us." And the killer space-robot spoke thoughtfully, his communication laser-fire rendered into comprehensible sound by the translator bugs hovering by or clinging to each of the gathered friends. "A fire." The robot's name was Arch-Beacon Clay. "I appreciate the symbolism. Graa, I will help you with a well-chosen word." Graa understood what Clay was about to do and pecked his hairy steed in the cheek. "Mr. Grumbles, full retreat!" The domesticated Homo erectus stumbled back from the pile of kindling just in time to avoid the burning light that blazed forth from Clay. "Fire!" communicated Clay, and there was fire. It was fall in the Zogreion. Specifically, in the nature reserve north and west of the city. Here, Twine's species had not converted the land into artificial mangrove swamp, but left it as a forest. The trees had turned dark and glassy as their leaves withdrew into their trunks, and unharvested reproductive netting littered the ground with orange tangles and curds. Quad-wing fliers called to each other as they soared south. A distant aircraft glowed pink with the light of a sun hidden behind the rim of this version of earth. The five friends had no reason to gather and talk, and that was exactly why they enjoyed it. Tonight they would not have to negotiate or charm. They could relax, set aside diplomacy and trade, and speak of more important things. "Have any of you seen the most recent broadcast of Heavy Bombardment?" asked Digeridoo. Graa nibbled on his steed's ear as he added more wood to the fire. "Is that the prequel series? My secretaries won't stop talking about it." "Yes!" squealed Twine around the rock in her mouth. "Are your secretaries Team Ceres or Team Eris? I'm Team Eris all the way. Woo! Boost that ice! Right?" "Right!" Under the mobile web of Hostess the spider, puppets dangled. One of them was shaped like Twine.2 Hostess manipulated this puppet, saying "Scatter those tholins!" With a bird-shaped puppet, however, she whispered an aside to Graa. "It's not as good as the original series, but I feel I have to keep up with it so I have something to talk to people about." Arch-beacon Clay sadly flickered his lasers. "I stopped watching Tensor fiction broadcasts a long time ago. It is as if the writers have never talked to a real person. It is as if they have lost their grip on meaning." "They are not paid to grip meaning," said Graa. "The show's writers are paid to extrude stories that the audience enjoys." "Yes." Digeridoo spoke out of the hole he was excavating in the forest floor. "You're overthinking, Clay. Just lie back and let the show wash over you. It doesn't have to make sense. It's just fun." "Don't you want something deeper?" asked Clay. Digeridoo stopped digging, closed his eyes and nostrils, and hugged himself with all four flippers. "No. There are things swimming in deep places." "Don't scare him," chided Hostess. Graa stretched his neck and raised his wings. "Belay that order!" Clay played lidar up and down Graa's feathered body. "You mean I should scare Digeridoo?" "Yes!" Graa paced back and forth across his steed's padded shoulder. "Fear is precisely the reason I invited you to this campfire gathering at the tipping point of autumn." "I thought you invited us so that we could roast treats over the fire," said Hostess. She manipulated threads, and clockwork arms hammered skewers of food into the ground. "Treats are only my secondary goal," said Graa. Digeridoo upended his tank of camping water into the hole he'd made. "You had an ulterior motive," he accused. "A trick!" Graa's throat-feathers bristled in smugness. "Now tell me: what scares you?" Silence around the campfire. Night creatures pipped to each others. Migrating fliers cried. The friends considered whether they were friendly enough to talk about this sort of thing. "I will lead the attack!" Graa crowed. "Now hear this! I am scared of food. I command you to imagine it!" Hostess visibly obeyed, releasing ratchets and tugging threads in her complex web to trigger memories and run simulations. The others just sat there, brains presumably working. Digeridoo closed his eyes. "You're perched above the carcass," said Graa. "You are entranced by the pattern of its blood on the snow. Vapors still rise from it. The meat is fresh! But this means that whatever killed the meat will still be near." As he talked, Graa lost his dominant posture. His feathers smoothed down and he tucked his wings tight to his sides. His voice took on the harsh qworks and triple-raks of fear. "If I stoop upon the meat, what will stoop upon me? How dare I? How dare I eat?" Graa huddled on his steed's shoulder. The domesticated Homo erectus whined and put his hand around his rider. Hostess shook her legs, rattling all four of her puppets. "Thank you for that tasty offering. I'll offer you my fear next: I'm scared that I'm not attractive." "Oh no, don't say that," said Twine. She rolled her rock, now heated, from the fire toward Digeridoo's mud bath. "You're very attractive." The rock went kshh and Digeridoo snorted in appreciation. "Thank you." The spider manipulated her puppets to give the various species' equivalents of appreciative bows. "You have all joined me for a meal, and I am grateful. But what about next time? Or the time after that? Every day I grasp my web and take up my puppets and wait for guests to come. I do my best to appeal to the widest range. I craft the most convincing decoys I can. But some days, my number of guests falls. What if it falls to zero? Someday it must, and what will I do when I have no one to mimic? Alone, who will I be?" "Interesting that your fear is loneliness," said Graa, who had calmed himself and his steed. "I would have thought you would be more afraid of being eaten by birds." Hostess twitched a leg, and one of her puppets flapped papier-mâché wings. "I have better ways to feed birds, my friend. Would you like a roasted fruit or a heated strip of meat?" Graa flapped down to grab both and cached them away where no-one else could see. "Who's next?" Twine twitched her single eye and raised her mouth above the mud-bath to chitter. "I am scared of staying huddled in my hive. Seeing the same clone-sisters every day, speaking about nothing that everyone does not already know. Forgetting the cold outside. And when the cold comes inside, I will not know how to fight it." Lasers sparkled from the anti-gravity cylinder that housed Arch-beacon Clay. "You and I are two ends of a tether, Twine. You fear falling in toward the heat, but I fear flying outward into the cold. Will I be unable to tolerate others? Will I throw away all my bindings and tumble, alone forever?" Hostess scuttled across her web and spun a symbolic thread linking it to Clay's cylinder. "Thank you," said the space-robot. "I wish I could feed you," said the spider. Clay spun himself, sparkling in his anti-gravity vacuum cylinder. "I absorb some energy from the fire, but what you give me is something better." "It's gotten dark," said Digeridoo, who was uncomfortable with emotional vulnerability. "That's the whole point of a campfire," said Twine. "We create a warm brightness to form the heart of a little hive, safe from the cold outer darkness." "Safe," said Hostess. "Exactly." Graa growled. "And yet there are treasures in the darkness, aren't there? To grab them, we must ride out. We must follow our fear, as if led by the pole." Clay understood, but those species without a magnetic sense required a little more clarification. "You think we should be led by our fear?" said Digeridoo. "Find things that scare you and then do them? That sounds foolish and dangerous. And I don't like all these metaphors." Twine vibrated her eyeball. "What danger? We are sophonts! We habitually leap between universes. We fear no predators. No starvation." "That's evidence in favor my argument," said Digeridoo. He was a bit hurt at Twine's aggressive tone. Hadn't he dug out all this nice mud for her? "We do not need to venture from our burrows in order to find food. We can stay safe, and let what we need come to us." "I confess I do like that idea," said Hostess the spider. Graa gave a kek kek kek call of frustration. "There the food lies, steaming in the snow below you. You hunger, you rage, you fear the glint of eyes in the darkness: predation. But you should also fear the rush of many wings coming up behind: starvation." "Metaphors again!" Digeridoo snorted. "Do I have to re-tune my translator?" Clay extended robot claws from his spherical shell. "You mean if you do not overcome your fear and snatch your prize, other people will steal it." "Exactly," said Graa. "You speak like someone who doesn't trust your neighbors," said Twine. "Yes. How many of us are killed by predators or natural disaster? How many of us are killed by each other? Why did we evolve intelligence in the first place. Not to outsmart hawks or blizzards, but to outsmart other sophonts." "You mean," said Hostess, "that we are our own monsters." "Yes!" Graa spread his tail, feathers on his legs and heads fluffy with dominance. "I win this conversation!" Clay spoke in a low-wattage murmur. "And yet you are the one who invited us here." Graa's feathers slimmed back down. "When the idea caught my eye, at first I blinked. My pride raised its wings, but behind those wings was fear. I recognized the fear, and oriented myself against it. I rode out to this campground, and I perch now before people not of my species. That is what a brave bird does." Twine's puppet bird gave the equivalent of applause while Clay aimed a laser at Digeridoo. "You accepted the invitation as well." "The queen says I need to get out more," grunted sea-beast. "They are expanding the burrow," explained Twine. "Digeridoo's colony needs money, as does my hive. This is why we network." "Ah," sighed the spider. "Networking." "I was most surprised of all to find you here, Hostess" Clay confessed. "Isn't it very difficult for you to travel from your restaurant?" Hostess moved her space-robot puppet in the equivalent of a nod. There was even a little electric light that flashed like a laser. "There is always a moment of terror when my web moves," she said. "Digeridoo might feel the same way flying, or Graa trapped in a watery burrow. Or in free fall..." She flashed her electric light again. "Clay, do you feel that terror when you look down, and see the ground does not move beneath you?" "I confess that I do." "And yet you're here with us." "And you've been to space." "Oh," said Digeridoo. "Space. I remember. Yes, that trip was terrifying, but nothing I've seen was more beautiful." Graa made a kek kek sound. "Alright! I accept your challenge! Next time, we can meet in a burrow." 1 The troll's name was Mr. Grumbles. 2 A one-eyed vacuum-cleaner with legs. This story was originally published on Royal Road

0 Comments

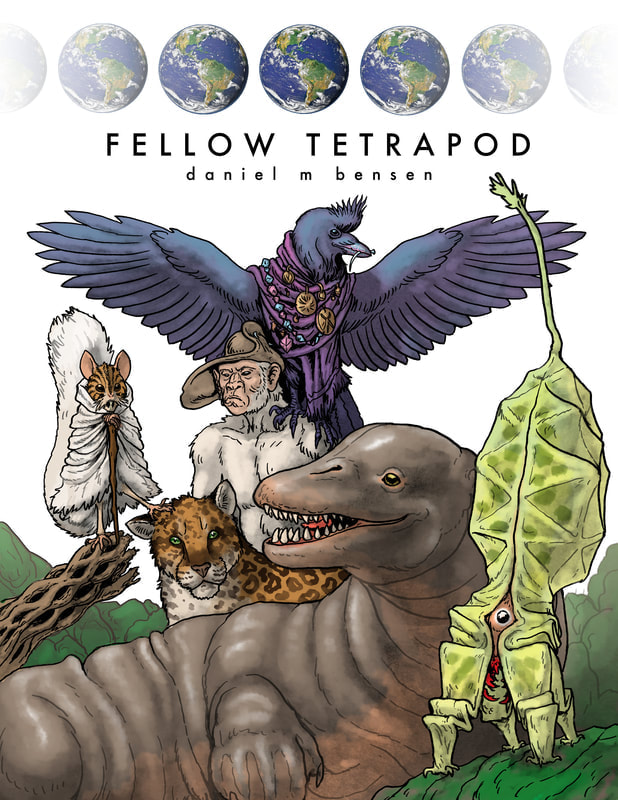

Alright, here we go! My speculative-evolution serial novel Fellow Tetrapod is finally live on Royal Road. Go check it out. If it looks like your sort of thing, follow the story. It updates every weekday. (if you want to know more...) Koenraad Robbert Ruis used to be a paleontologist, but now he's a cook at the United Nations embassy to the Convention of Sophonts. His bosses must negotiate with intelligent species from countless alternate earths, and Koen must make them breakfast. It turns out, though, that Koen is rather better at inter-species communication than any other human in this world (all nine of them). Everyone loves to eat (certain autotrophs excepted). Fellow Tetrapod is an speculative-evolution office comedy about food preparation, diplomacy, and what it’s like to be a talking animal. Serialized every weekday on Royal Road and (one week earlier) Patreon Cover art by Simon Roy. Illustrations by Tim Morris.

This is a bit of an experiment. Before I mediated a panel of the speculative biology of fantasy, I asked Tumblr what they wanted to learn about. I got a ton of questions, and now I've answered one of them.

Davrial asked: Would a griffon be classified as an avian, or a mammal? Here's my answer with accompanying pictures. Energy curdled back into mass as the ship translated out of light speed. After a pause for the crew to get used to experiencing time again, the ship’s instruments extended.

From the crew’s perspective, they’d finished an extensive survey of this part of space just a moment ago. For this part of space, however, 600 years had passed, so it was important to make sure nothing had changed. Something had. “It used to be a star like the sun,” explained the astrophysicist, whose name was Gaviria. “It had a family of planets ranging in size from a little larger than Earth to a little smaller than Neptune, all of them orbiting closer than the orbit of Jupiter.” Marletta, the astrophysicist, spoke over Gaviria in his excitement. “So far, so similar to many other star systems. Really, it’s closer to the galaxy’s standard average than the Solar System.” “Or it was when we translated to light,” said Gaviria. “But?” asked Zhang. Once a biochemist, Zhang had recently been elected to the post of “Social Coordinator,” or as he called himself, “cat herder.” “Its planets have shrunk,” said Gaviria. “Huh.” Zhang wondered why he was having this conversation. Aha. There it was. “You want me to authorize an away team.” In free fall as he was, Marletta could not jump up and down with excitement. The best he could do was anchor himself to a hand-rail and vibrate in place. “It’s close. It’s super close!” Zhang looked at Gaviria, who said, “Point nine eight light years.” “Would a two-year-ship-time trip fit our flight plan?” Zhang’s question was directed at the ship’s computer, which cleared the mission. Soon, the three of them were packed and in their landing pod, which the ship translated into light. The team was away. *** After either a year or no time at all, the landing pod re-materialized above a planet. Zhang, Marletta, and Gaviria watched the hazy, blue-white ball flicker in their portholes. As their pod translated itself into a safe landing trajectory, the planet vanished and reappeared, changing position and orientation. It grew closer. Now, the planet filled all the portholes on one side of the pod. The diamond light of its home star limned its upper edge. Now, that light was tinged red by atmosphere, and the edge had become the horizon. The horizon developed mountains. Finally, the pod settled, the planet became the ground, and Gaviria, Marletta, and Zhang walked out onto it. Zhang hopped experimentally, feeling his suit flex under the extra gee. He couldn’t smell anything except his own canned air, but his mics picked up the sound of running water, wind over rocks, and a distant bass pulse that might be surf. They’d touched down on a hill overlooking a floodplain, where a river flowed into an ocean. The sun rose above the mountains on the other side of the plain, casting pink-yellow light onto clouds, folded rocks, and the forest growing out of the river. The plants, if they were plants, had no leaves, branches or trunks. The green, blunt-nosed cones simply sat there, their roots – if they had roots – invisible under the water. They might still prove to be some strange kind of geology, but Zhang allowed himself to take a leap of faith, and sighed, “Life.” Part of the reason Zhang had accepted the post of cat herder was that there wasn’t usually much call for a biochemist. It wasn’t the first extraterrestrial biosphere that the Von Neumann Fleet had discovered, but it was a first for his individual ship. “Samples samples aha,” Gaviria hummed to herself. She headed for a cone-plant growing in a nearby stream. Marletta looked out over the blue ocean and green floodplain. “Life how? Six hundred years ago, this place was a sub-Neptune.” “It’s much closer to its star than our Neptune,” said Zhang. “Right?” Marletta flapped his hands. “And with a denser core. And not as close as Earth…really, it was intermediate between Earth and Neptune.” “Which is unusual?” “Well, yes. Usually you either have a terrestrial planet like Earth: a secondary atmosphere out-gassed from the rock.” Marletta held his hands apart, as if measuring a grapefruit. “Or,” He spread his hands out to the diameter of a beach ball. “Or, you get a gas giant like Neptune, with an envelope of hydrogen and helium gathered out of the primordial matter that built its star. Those light gasses spread out farther, so the planet looks bigger from space.” He moved his palms inward, the volume between them now the size of basketball. “But then over time, heat from the planet and the star would have blown that primordial atmosphere away. That’s why we assumed that the intermediate diameters, like the one-point-five Earth diameter this planet used to have, were so rare.” “Rarer now!” said Gaviria. She chipped away at the green cone-plant with her multi-tool. The surface of the organism was as hard as the heat shielding of their landing pod. “Since we left Earth, every planet in this system has shrunk down.” Zhang watched Gaviria work. “And in only six hundred years,” he mused. “I’m assuming that’s much faster than any stellar or geological process could account for.” “Don’t jump to conclusions,” said Gaviria. But Zhang didn’t have to line up his evidence for a review board. He was a cat herder now, and he could jump to whatever he wanted. “Marletta, did the observations we made from Earth indicate oxygen in this planet’s atmosphere?” “Well, we don’t know,” said Marletta. “We never recorded any absorption spectra through the original atmosphere. All we have are the transit and radial velocity data that told us the size and mass of this system’s planets. But…” His brain caught up with his mouth. On Earth, Marletta would have spun around to face Gaviria and her cone-plant. In two gees, he wobbled like a penguin, but eventually got himself turned in the right direction. “You mean photosynthesis?” “How much longer?” Zhang asked Gaviria. His logic was leading him into uncomfortable places. Gaviria gave her cone-plant another whack with her multitool, which didn’t even scratch the surface. “Just let me get my sample. It’s not going to go off right now, just because we’re talking about it.” “‘Go off,'” Zhang repeated. Marletta thought out loud. “Water and carbon dioxide go in, oxygen and carbohydrates come out. O2 gas rises to mix with the H2, and now every time there’s a bolt of lightning or other spark…” “Well,” said Gaviria, “boom.” Marletta swore in English, and Zhang made a decision. “We need to go.” “Stop being paranoid, this all happened hundreds of years ago.” Gaviria scratched at the cone again. Marletta stopped, his colleague’s assumptions overriding his sense of self-preservation. “Wait. That’s still not fast enough. The entire atmosphere couldn’t have, uh, explosively oxidized in only six hundred years.” Zhang answered the implied question. “There must have been biological processes actively speeding things up. Sequestrating the hydrogen? Controlling the rate of reaction?” He shook his head, remembering he was supposed to be herding these cats. “Let’s go, Gaviria. We can print out better tools on the pod.” After a light-speed jump into deep space, he added silently. “I suppose so,” Gaviria reluctantly put away her multitool and hoisted herself out of the stream. Marletta couldn’t snap his fingers in his suit, but he tried. “And it didn’t just happen on this planet, did it? Every planet in the system lost its hydrogen atmosphere within the same six-hundred-year window!” “Panspermia!” crowed Gaviria from the bank. Zhang groaned because he had always hated the idea of panspermia. Also, because steam was rising from the cone-plant behind his geologist. *** It was a good thing, they decided later, that Gaviria hadn’t been able to crack the ablative shielding on the cone-plant. If she had, it could well have exploded. As it was, though, the plant only launched. Back in the safety of their pod, the three humans watched as the green, ceramic-shelled organism lifted into the sky on its pillar of fire, and began its mission to spread life to other stars. This story was inspired by William Misener’s “To Cool is to Keep: Residual H/He Atmospheres of Super-Earths and sub-Neptunes.” Thanks go out to him and everyone at the 2020 NASA Exoplanet Science Institutes Exoplanet Demographics conference. This story was published in “Heavy Metal Jupiters,” the zine of the Exoplanet Demographics 2020 conference. “People need a way to stave off the constant possibility that common understanding may break down.”

— N.J. Enfield, How We Talk Royal tangs wobbled serenely between the softly undulating tentacles of sea anemones. Bubbles rose in a shimmering curtain. The filter hummed. I watched the tropical fish in their tank and tried to control my breathing. “Waffles?” I said. “The ambassador is running late because of your waffles?” Lucas turned red. “I did ask him to find a source of malt for the batter, yes.” “I don’t know what either of those words mean,” I flung up my hands. “And I don’t care. You stupid boys and your stupid Western Cooking projects!” “He really liked my waffles,” said Lucas, immodestly. I looked back at the fish, which failed to soothe me. “Translator?” I said in Chinese. “Estimated arrival time for Ambassador Wang?” “34 minutes,” answered the bumble-bee-sized robot. “Estimated arrival time for the representative of the Monumental Chamber of Commerce?” “Zero minutes.” The doorbell buzzed. “Miss?” came the voice of the doorman. “There’s a…a giant…uh…a sort of giant…” “Yes, yes, send him up.” I turned to Lucas and said in English. “Okay, so we stall him.” “Oh,” Lucas looked at the floor. “We.” “Yes!” “I was just going to serve you lunch. Orata al cartoccio and mousse au chocolat.” “Translator?” “Sea bream to the paper bag,” supplied the little robot, “and foam at the chocolate.” “Sounds delicious,” I said, “but I need you in your capacity as biologist, Lucas. I don’t even know what a Monumental looks like.” I thought back to the briefing Lucas had sent me the week before. “Some kind of whale? Some kind of hippo?” He wobbled his head. “You’re thinking of the word ‘whippomorpha.’ Yes, the Architects of Stable Monuments evolved from stem-whippomorphs. That’s the clade that includes everything that evolved from the most recent common ancestor of both whales and hippos, but left no descendants on our version of Earth. The Monumental Earth experienced an Ice Age during the Eocene…” I looked at the rising floor readout of the elevator. “Will he be poisoned by fish in a bag and chocolate?” “No.” I thought back to other diplomatic/biological faux pas of the past. “Will his sweat poison us?” “No.” “Will he fit through the door?” “Um,” said Lucas, and the elevator opened. A sound rolled into the lobby of the United Nations Embassy to the Convention of Sapient Species, part scream, part rumble, part didgeridoo. “Let me immediately go away from this very small coffin, otherwise I will put you monkeys in a hole and cover you with a pile of manure!” the translator translated for the representative of the Monumental Chamber of Commerce. The forward half of the representative flopped out of the elevator and hit the floor with a heavy crack. He did not look much like a hippo or a whale. He looked like a sausage riding a scateboard. A sausage with whiskers and ears at one end and a flat beaver-like tail at the other, now visible as the enormous creature paddled into the lobby on four limbs that could have been hooves, hands, or flippers. He was wrapped in some sort of tough, transparent plastic and three pairs of wheels lined his belly, like the castors on an easy chair. He smelled like clay and sea water. Another didgeridoo blare, which the translator rendered as. “I apologize. My calling out was caused by discomfort of the body. I will not let it affect my judgement. I am (untranslatable), who are you?” I introduced myself and Lucas, and said, “Translator, flag name of interlocutor and assign temporary translation as ‘digeridoo.’ Confirm?” “Confirmed.” “I am very happy and ashamed. I go with you see your husband!” trumpeted Didgeridoo. “Clarify?” I asked, making another promise to myself that I would murder our current translation coder as soon as I found someone who could replace him. “I want you to show me your husband.” “Lucas? What’s he talking about? What are the mating habits of Monumentals?” “Um,” he said. “Oh! Polyandrus! High-ranking females have a harem of husbands — usually brothers or first cousins — who they send out to do things for them.” “Translator, flag word ‘husband’ in present Monumental language and reassign translation to ‘underling.'” I wanted for confirmation and addressed our guest. “Should I take you to my underling?” “Yes.” Didgeridoo opened his mouth, displaying peg-like teeth. I assumed that was a sign of impatience. “I know you Nationals are abnormal of custom, but with female strangers, conversation me very much uncomfortable.” “Lucas?” I said. “Right, the public sphere is males doing business with each other in the name of their wives, which means,” he glanced at me, “it might help to tell Didgeridoo that I’m your husband?” Digeridoo’s broad ears swiveled toward Lucas. “Him? This stinky male is your husband?” They flattened against the Monumental’s skull. “I am sorry, I believe your other brothers are more fragrant, but their skills are lower. I am very with pleasure because you have introduced me to your dear wife.” He raised his front flippers and made a motion with them as if doing the breast stroke. “New topic: our meeting. Where is it?” I looked down at the huge, cigar-shaped sophont on the floor, and thought of the conference room with its table and chairs. “Why, our meeting is right here.” The ears jerked back toward me and with a squeal of little wheels, Digeridoo rolled onto his back and squirmed like a playful kitten. “I am very happy because you speak to me. Even if you are not my wife, you respect me.” He rolled back over and panted for a moment before addressing Lucas. “New topic: I will relax. How is it I climb in northeast side furniture?” We looked into the northeastern corner of the room, which was entirely occupied by the fish tank. “Clarification,” I said. “You want to lie down on the couch?” I pointed at the couch next to Didgeridoo. Didgeridoo didn’t track my finger with his ears, but the translator rumble-squeaked something and he gaped, wiggling. “I don’t want to tell you that you are not correct. You stretched your hoof in the direction of a dry object. It doesn’t have roots. I am pointing to the furniture in the northeast corner of the room. It smells like fish. I like it. However, it is very high from the ground. I do not know how to climb in.” “It’s a fish tank,” I said. “It isn’t furniture. It isn’t for sitting in.” When the hell was Wang going to arrive? Waffles! Digeridoo flipped back over onto his back. “I feel very disappointed and not comfortable. I feel very ashamed.Because you are a woman, please don’t talk to me.” Lucas looked from the quivering belly of the Monumental to me. “I think you intimidate him.” I sighed. “So you talk to him. Tell him I’m sorry we don’t have a suitable place for him to rest, but we would be happy to serve him lunch while we wait for the ambassador.” I resisted tapping my feet while Lucas relayed the message and Digeridoo flipped back over, castors screeching across the floor. “What kind of food did you make fermented for me?” Wrinkled nostrils opened and snuffled between Digeridoo’s ears. “I want to confirm that the food is not your nauseating smell’s source.” I groaned and Lucas sniffed his fingers. “I smell chocolate and baked fish.” Digeridoo flattened his ears and slapped his tail on the floor. “The fish has been fired in a kiln! National, you must clarify that you put the fish in a kiln, and you have smeared the ashes of the fish on your flippers, and now you are talking to me! Don’t you know that my wife writes letters to the Pyramid of the River Delta, which is filled with Gleaming Specks of Mica? No, you must know! You are making a lot of damn pyramids on this damn Salmon Festival!” Lucas looked at me with panic in his eyes. I may not have had time to read up on Monumental Biology, but that was because I had prioritized the spec sheets they had given us and the terms of the contract they were offering. Money and future trade considerations in exchange for the manufacture of millions of devices called, by the translation software, “Toy Pyramids of the Salmon Festival.” Lucas’s fancy fish-in-a-bag lunch had gravely offended the religious sensibilities of our guest. “Uh. No,” I said. “That was…a terrible accident. No baked fish.” Then, before Digeridoo could show me his belly again, “tell him, Lucas.” “It was a mistake?” he said. “And go get the chocolate mousse and the sample toy pyramid.” “Just a moment, sir.” Lucas ducked through the door into the embassy. I smiled awkwardly at Digeridoo, who wriggled awkwardly back at me. “What sample toy pyramid?” called Lucas from the back rooms. “The one we had manufactured on Earth,” I called back. “It’s a decoration for the Monumentals’ equivalent of New Year’s. It’s shaped like a pyramid!” Lucas rushed back into the foyer with three small plastic glasses, spoons, and the toy pyramid, which looked like the Antikathera Mechanism had mated with a Rubix Cube. Digeridoo sniffed, running his whiskers over Lucas’s out-thrust hands. “What is this paste of bitter grass? I will take the toy pyramid of the day of the salmon.” He delicately grabbed the pyramid between his front teeth and rolled over onto his side, curling around the toy and prodding at it with whiskers, tongue, tail, and all four limbs. “I told you to cook something that wouldn’t poison him,” I hissed at Lucas. “I did!” he said. “There’s nothing in his biochemistry that should have a problem with sea bream or chocolate. Nothing in the literature said Monumentals think cooked fish is taboo!” “Maybe it’s only the Monumentals whose wives write letters to the Pyramid of the Mica Delta,” I said. Lucas nodded glumly. “We’re going to need to do a lot more cultural research if we want to make these people’s Christmas ornaments for them.” “I am very satisfied so far,” said Digeridoo. “Just now give me some mud.” “Um,” said Lucas. “Clarify?” “Mud!” hooted Digeridoo. “Dark mud! Silt! Soft mud! Loose mud! [unassigned word]! Clay and water and organic granules! I assume the mud in the room’s northeast corner. Please give me that mud, so that I can test the toy you made for me. Is the toy effective?” “The specifications didn’t say it needed to work in mud,” I said. “No, never mind, don’t roll over.” I looked at the fish tank, and sand that covered its floor. I pictured that sand in the pyramid toy’s many tiny gears. “Lucas, give Digeridoo your mousse. Tell him that’s the mud he wants. And don’t you roll over at me, either.” Lucas sniffed, pulled his lower lip back in, and gave the Monumental his chocolate mousse. “Bitter grass,” mumbled Digeridoo. “I am unhappy because of this smell.” So was I at the squelching noises. “However, it is apparent that the toy operates well in normal conditions,” Digeridoo concluded. “I am very happy because your species meets our lowest standards of manufacture. We will eat, then we will discuss payment.” “Eat?” said Lucas. “Yes!” said Digeridoo. “Food is a negotiation prerequisite condition.” Lucas looked at me. “Translator,” I asked, “when will the ambassador arrive?” “In 10 minutes.” I turned and looked at the fish tank. A blue tang swam by. “Ask him,” I told Lucas, “if he would mind a raw fish.” |

AuthorDaniel M. Bensen Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed